Introduction: Unlocking Kernel Superpowers

The Linux kernel, the heart of countless operating systems and devices, has long been a powerful but somewhat enigmatic realm. Modifying its behavior or gaining deep insights into its inner workings traditionally required complex kernel module development or even direct kernel source code changes – tasks fraught with risk and steep learning curves. But what if there was a way to safely and dynamically extend the kernel’s capabilities at runtime, without these hurdles? Enter eBPF (Extended Berkeley Packet Filter).

Once a niche tool for packet filtering, eBPF has evolved into a revolutionary technology that is reshaping how we approach observability, networking, and security in Linux environments. It acts like a sandboxed, event-driven virtual machine within the kernel itself, allowing developers and system administrators to run custom programs that can inspect and manipulate system behavior with unprecedented granularity and efficiency. From high-performance networking and sophisticated security monitoring to in-depth application tracing and performance analysis, eBPF is unlocking new possibilities and empowering users with what many have dubbed “kernel superpowers.”

This blog post aims to demystify eBPF. We’ll explore its origins, delve into its core architecture, and showcase its transformative impact across various domains. Whether you’re a seasoned kernel developer, a DevOps engineer, a security professional, or simply a tech enthusiast curious about the next wave of innovation, join us as we uncover how eBPF is making the Linux kernel more programmable, observable, and secure than ever before. We’ll look at real-world use cases, popular tools that leverage eBPF, and how you can start exploring this exciting technology yourself. Get ready to see the Linux kernel in a whole new light!

What is eBPF? From Packet Filter to Kernel Virtuoso

eBPF, or Extended Berkeley Packet Filter, is a powerful technology originating within the Linux kernel that allows sandboxed programs to run in a privileged context, such as the operating system kernel itself. Think of it as a tiny, highly efficient, and safe virtual machine embedded directly into the kernel. This allows developers and system administrators to extend the kernel’s capabilities dynamically, at runtime, without needing to change the kernel’s source code or load potentially risky kernel modules.

Historically, the operating system kernel has always been the ideal place to implement functionalities like networking, security enforcement, and system observability. This is because the kernel has a complete view and control over the entire system. However, modifying the kernel is a complex and slow process. Kernels are designed for stability and security, meaning innovation at the kernel level has traditionally been slower compared to user-space applications.

eBPF fundamentally changes this equation. By allowing sandboxed programs to run within the kernel, application developers can add new functionalities to the operating system on the fly. The kernel guarantees the safety and efficiency of these eBPF programs through a rigorous verification process and a Just-In-Time (JIT) compiler, which translates eBPF bytecode into native machine code for near-native execution speed.

The Evolution from BPF to eBPF:

The story of eBPF begins with its predecessor, BPF (Berkeley Packet Filter), which was introduced in a 1992 paper by Steven McCanne and Van Jacobson. The original BPF was designed primarily for filtering network packets efficiently in user space, for tools like tcpdump. It provided a simple, register-based virtual machine that could execute filter programs directly on network data.

Over the years, the potential for a more generalized in-kernel virtual machine became apparent. Alexei Starovoitov led the effort to significantly extend BPF, transforming it into the eBPF we know today. This extension, merged into the Linux kernel around version 3.18 (with core functionalities maturing by Linux 4.4), expanded BPF in several crucial ways:

- 64-bit Registers and More Registers: eBPF uses 64-bit registers (ten general-purpose registers plus a read-only frame pointer) compared to BPF’s two 32-bit registers, allowing for more complex programs and easier interaction with 64-bit architectures.

- Increased Programmability: eBPF supports a much richer instruction set, including calls to a set of pre-defined kernel helper functions and the ability to call other eBPF functions.

- Maps: A crucial addition was eBPF maps – versatile key/value stores that allow eBPF programs to store and share state, not only among themselves but also with user-space applications. This enables sophisticated data collection, aggregation, and communication.

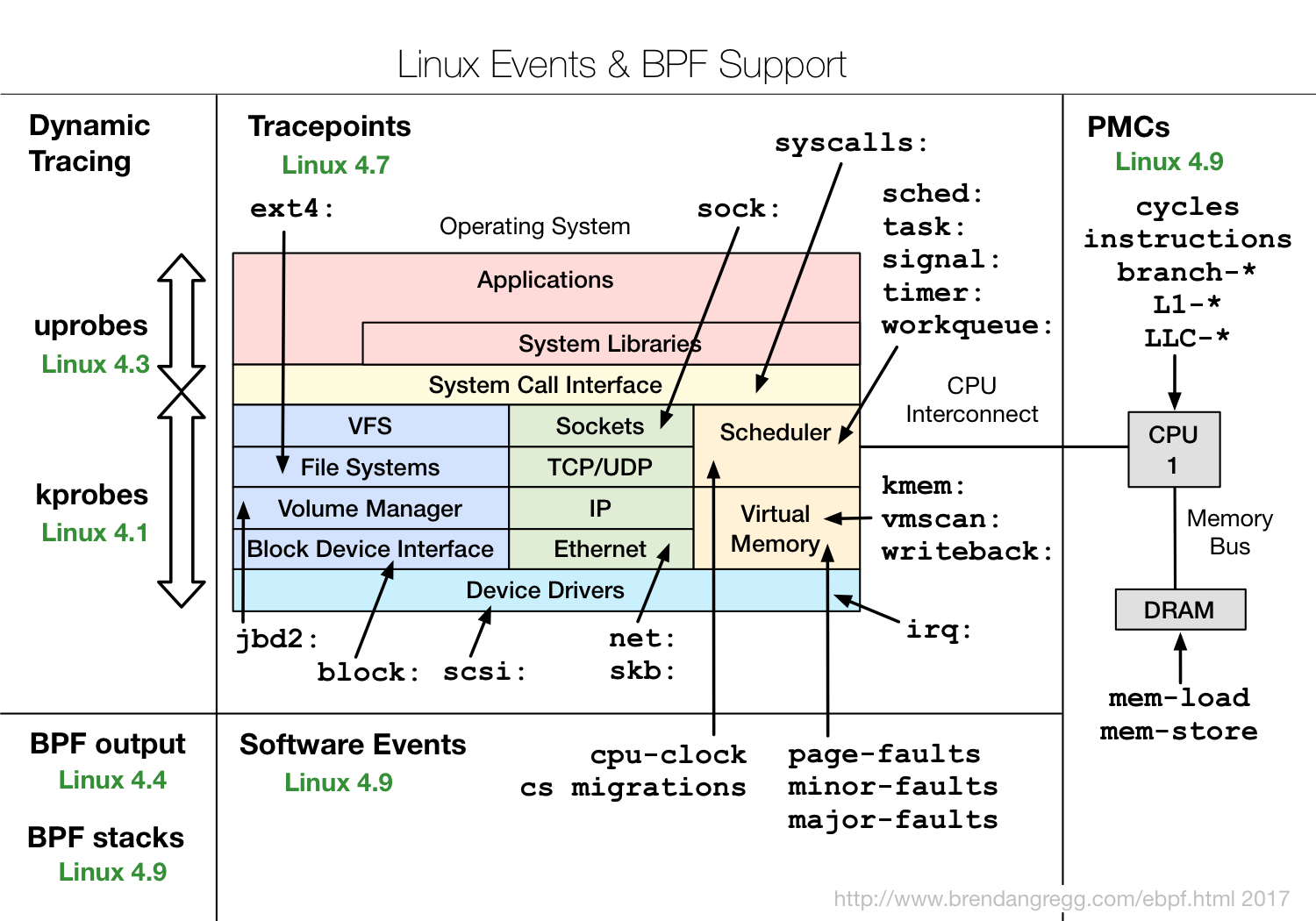

- Wider Range of Hooks: While BPF was primarily for network packets, eBPF programs can be attached to a vast array of hook points within the kernel, including system calls, kernel functions (kprobes), user-space functions (uprobes), tracepoints, network events (XDP, TC), security hooks (LSM), and more. This versatility is what makes eBPF applicable to so many different use cases.

It’s important to note that the term “BPF” is now often used interchangeably with “eBPF” in documentation and discussions. The original BPF is sometimes referred to as cBPF (classic BPF) to avoid confusion.

The significance of eBPF lies in its ability to make the kernel programmable in a safe, efficient, and dynamic manner. It has spurred a wave of innovation, leading to next-generation tools for networking, observability, and security that were previously difficult or impossible to build. Today, eBPF is a cornerstone technology in cloud-native environments, high-performance computing, and embedded systems, driving advancements across the tech industry.

Understanding eBPF Architecture: A Look Under the Hood

![]()

To truly appreciate the power and safety of eBPF, it’s essential to understand its core architectural components. These components work together to allow custom programs to run securely and efficiently within the Linux kernel.

(Image source: ebpf.io - A simplified overview of eBPF architecture)

(Image source: ebpf.io - A simplified overview of eBPF architecture)

The eBPF architecture can be broken down into several key elements:

-

eBPF Programs and Bytecode: At its heart, eBPF involves programs written in a restricted C-like language. These programs are then compiled, typically using a compiler like Clang (which has an LLVM backend for eBPF), into eBPF bytecode. This bytecode is what gets loaded into the kernel.

-

Hooks and Event-Driven Execution: eBPF programs are event-driven. They don’t run continuously but are triggered when specific events occur at predefined hook points within the kernel or user space. These hooks can be:

- Kernel Probes (kprobes): Allow dynamic instrumentation of almost any kernel function (entry or exit).

- User Probes (uprobes): Allow dynamic instrumentation of user-space application functions.

- Tracepoints: Statically defined trace points in the kernel code, offering a stable API.

- System Calls: Hooks at the entry and exit of system calls.

- Network Events: Hooks at various points in the network stack, such as XDP (eXpress Data Path) for early packet processing at the driver level, or TC (Traffic Control) for packet manipulation further up the stack.

- Security Modules (LSM hooks): Allow eBPF programs to implement security policies.

- cgroup hooks: Attach eBPF programs to cgroups for resource control and monitoring. When an event at a registered hook occurs, the corresponding eBPF program is executed.

-

The Verifier: This is arguably the most critical component for ensuring the safety of eBPF. Before any eBPF bytecode is loaded and executed, it must pass a rigorous verification process. The verifier performs static analysis on the eBPF program to ensure it won’t harm the kernel. Key checks include:

- No Unbounded Loops: The program must be guaranteed to terminate. The verifier checks for loops and ensures they have a bounded number of iterations.

- Valid Memory Access: Programs cannot access arbitrary kernel memory. They can only access their own stack space, context data (like packet data for network programs), and data stored in eBPF maps.

- No Null Pointer Dereferences: The verifier tracks pointer states to prevent crashes.

- Correct Register State: Ensures registers are used correctly and types are consistent.

- Privilege Checks: Ensures the process loading the eBPF program has the necessary capabilities. If any of these checks fail, the verifier rejects the program, preventing it from being loaded.

-

Just-In-Time (JIT) Compilation: Once an eBPF program passes verification, the kernel’s JIT compiler translates the eBPF bytecode into native machine code for the specific CPU architecture (e.g., x86-64, ARM64). This JIT compilation step is crucial for performance, allowing eBPF programs to run nearly as fast as natively compiled kernel code.

-

eBPF Maps: Maps are a fundamental data structure in eBPF. They are efficient key/value stores that reside in kernel memory and can be accessed by eBPF programs and also by user-space applications via system calls. Maps serve various purposes:

- State Sharing: Allow different eBPF programs, or eBPF programs and user-space applications, to share data.

- Data Collection: eBPF programs can collect statistics or event data and store it in maps for user-space tools to retrieve and analyze.

- Configuration: User-space applications can use maps to configure the behavior of eBPF programs. eBPF supports various map types, including hash tables, arrays, LRU (Least Recently Used) caches, ring buffers (for efficient event streaming), stack traces, LPM (Longest Prefix Match) tries (for IP routing), and more. Each map type is optimized for specific use cases.

-

Helper Functions: eBPF programs cannot call arbitrary kernel functions directly, as this would create dependencies on specific kernel versions and pose security risks. Instead, they can call a set of well-defined, stable kernel functions known as

helper functions. These helpers provide a stable API for eBPF programs to interact with the kernel, performing tasks like: * Accessing eBPF maps (lookup, update, delete elements). * Getting current time and date. * Generating random numbers. * Manipulating network packets (e.g., resizing, adjusting headers). * Getting process/cgroup context information. * Performing tail calls. The set of available helper functions is carefully curated and continues to evolve, expanding the capabilities of eBPF programs.

-

Program Types: eBPF programs are categorized by “program types,” which define where the program can be attached (i.e., which hooks it can use) and what kind of context data it receives as input. The program type also dictates which helper functions are available to the program and what the expected return value signifies. Examples of program types include

BPF_PROG_TYPE_KPROBE,BPF_PROG_TYPE_TRACEPOINT,BPF_PROG_TYPE_XDP,BPF_PROG_TYPE_SCHED_CLS(for TC),BPF_PROG_TYPE_SOCKET_FILTER, andBPF_PROG_TYPE_LSM. -

Tail Calls and BPF-to-BPF Calls: eBPF programs can be composed together.

- Tail Calls: Allow an eBPF program to jump to another eBPF program, effectively replacing its own execution context with the new program. This is useful for creating complex program chains or implementing dispatch tables.

- BPF-to-BPF Calls: Allow an eBPF program to call another eBPF program as a subroutine. The called function executes within the same context and then returns to the caller. This promotes code reuse and modularity.

-

Object Pinning (BPF File System): To allow eBPF maps and programs to persist beyond the lifetime of the process that loaded them, they can be “pinned” to a special BPF file system (bpffs). This allows different user-space processes or even the kernel itself to access and reuse these eBPF objects.

Together, these architectural components create a robust and flexible framework. The verifier ensures safety, the JIT compiler ensures performance, maps provide stateful capabilities, helper functions offer controlled kernel interaction, and the diverse hook points allow eBPF to be applied to a wide array of problems. This architecture is the foundation upon which the diverse use cases of eBPF are built.

Key Use Cases of eBPF: Revolutionizing Kernel Capabilities

The flexible and secure programmability that eBPF brings to the Linux kernel has unlocked a wide array of powerful use cases. Its ability to safely inspect and manipulate system behavior at a low level, with minimal overhead, has made it an indispensable technology in modern computing. Let’s explore some of the key areas where eBPF is making a significant impact:

1. Observability and Tracing

Understanding what’s happening inside a complex system is crucial for troubleshooting, performance optimization, and security. eBPF provides unprecedented visibility into both kernel and user-space applications.

- Performance Monitoring & Profiling: eBPF can be used to collect detailed performance metrics, such as CPU usage, memory allocation, I/O operations, and function latencies, with very low overhead. Tools can aggregate this data in-kernel using eBPF maps, providing rich insights without overwhelming the system with raw event data. This allows for fine-grained profiling of applications and the kernel itself to identify bottlenecks.

- Application Tracing: Developers can use eBPF (often via tools like

bpftraceor BCC) to dynamically trace function calls, system calls, and other events within their applications or third-party libraries without modifying their code or restarting processes. This is invaluable for debugging complex issues and understanding application behavior in production environments. - System-Wide Tracing: eBPF allows for tracing events across the entire system, from hardware interrupts to application-level requests. This holistic view helps in understanding interactions between different components and diagnosing system-wide performance problems.

- Custom Metrics Collection: Instead of relying on pre-defined counters, eBPF enables the creation of custom metrics tailored to specific needs. For example, one could count specific types of network errors, track the latency of particular database queries, or monitor resource usage by specific container workloads.

2. Networking

eBPF’s origins are in packet filtering, and it continues to be a game-changer in the networking space, offering high performance and programmability.

- High-Performance Packet Processing (XDP & TC):

- eXpress Data Path (XDP): eBPF programs can run directly in the network driver, at the earliest possible point when a packet is received. This allows for ultra-fast packet processing, such as dropping malicious traffic, performing load balancing, or routing packets before they even reach the kernel’s main networking stack. XDP is often used for DDoS mitigation and building high-speed virtual network functions.

- Traffic Control (TC): eBPF programs can also be attached to the Traffic Control (TC) ingress and egress hooks of network interfaces. This allows for more sophisticated packet manipulation, classification, and queuing, as TC programs have access to more packet metadata (e.g., socket information).

- Load Balancing: eBPF, particularly with XDP and TC, is used to build highly efficient and scalable load balancers. Projects like Cilium and Katran (by Meta) leverage eBPF for Layer 3/4 load balancing directly in the kernel, outperforming traditional IPVS-based solutions.

- Network Policy Enforcement & Segmentation: eBPF can enforce fine-grained network security policies by inspecting and filtering traffic based on various criteria (IP addresses, ports, labels, HTTP headers, etc.). This is a cornerstone of container networking solutions like Cilium, enabling microsegmentation and secure communication between workloads.

- Protocol Parsing and Manipulation: eBPF programs can parse custom network protocols or add new protocol handling logic without modifying the kernel. This is useful for network monitoring, custom tunneling solutions, or implementing new network services.

3. Security

eBPF provides powerful primitives for building advanced security monitoring and enforcement tools.

- Intrusion Detection and Prevention (IDS/IPS): By monitoring system calls, network activity, and file access in real-time, eBPF can detect suspicious behavior indicative of an attack. XDP can be used for high-speed packet filtering to block known malicious IPs or traffic patterns.

- Runtime Security Enforcement: eBPF can enforce security policies at runtime, such as restricting access to sensitive files, preventing certain system calls, or limiting network connections for specific processes or containers. Tools like Falco and Tetragon (part of Cilium) use eBPF for runtime threat detection and enforcement.

- System Call Filtering and Auditing: eBPF allows for fine-grained filtering and auditing of system calls made by applications. This can be used to create sandboxes, restrict application capabilities, and generate detailed audit logs for compliance and forensics.

- Container Security: In containerized environments, eBPF provides deep visibility into container behavior and allows for the enforcement of security policies at the container level, isolating workloads and protecting the host kernel.

- Rootkit Detection: By monitoring kernel-level events and data structures, eBPF can help detect the presence of rootkits or other kernel-level malware.

These use cases are not mutually exclusive; often, eBPF solutions combine elements of observability, networking, and security. The ability to program the kernel safely and efficiently has opened the door to a new generation of tools that are more powerful, more flexible, and less intrusive than their predecessors. As the eBPF ecosystem continues to grow, we can expect even more innovative applications to emerge.

Popular eBPF Tools and Projects: The Ecosystem in Action

The power and flexibility of eBPF have given rise to a vibrant ecosystem of tools and projects that leverage its capabilities. These tools abstract away some of the complexities of writing raw eBPF code and provide ready-to-use solutions for various observability, networking, and security challenges. Here are some of the most prominent players in the eBPF landscape:

1. BCC (BPF Compiler Collection)

- What it is: BCC is a rich toolkit for creating efficient kernel tracing and manipulation programs, primarily for Linux. It provides a Python (and Lua) frontend and integrates with LLVM/Clang to compile and load eBPF programs. BCC makes it much easier to write ad-hoc eBPF programs for performance analysis and troubleshooting.

- Key Features: Includes a vast collection of pre-built tools for various tasks (e.g.,

biolatencyfor block I/O latency,tcplifefor tracing TCP connections,execsnoopfor tracing new process execution). It also provides libraries for developing custom eBPF tools. - Use Cases: Performance analysis, system troubleshooting, learning eBPF programming concepts.

2. bpftrace

- What it is:

bpftraceis a high-level tracing language for Linux eBPF. It uses a syntax inspired by DTrace and awk, making it relatively easy to write powerful one-liners and short scripts for custom tracing. - Key Features: Concise syntax, powerful filtering and aggregation capabilities, access to kernel dynamic tracing (kprobes), user-level dynamic tracing (uprobes), and tracepoints.

- Use Cases: Live system debugging, performance analysis, exploring kernel and application behavior.

3. Cilium

(Image source: cilium.io)

(Image source: cilium.io)

- What it is: Cilium is an open-source project that provides eBPF-powered networking, security, and observability for cloud-native environments, particularly Kubernetes. It leverages eBPF at the core of its data plane.

- Key Features:

- Networking: High-performance CNI (Container Network Interface) for Kubernetes, identity-based connectivity, multi-cluster networking, efficient load balancing (using eBPF instead of kube-proxy).

- Security: Identity-based security policies, API-aware security (e.g., filtering HTTP, gRPC calls), transparent encryption, runtime threat detection.

- Observability: Deep visibility into network flows, application protocols, and system calls, often visualized through Hubble (Cilium’s observability platform).

- Use Cases: Kubernetes networking and security, microservices communication, cloud-native observability.

4. Falco

- What it is: Falco is a cloud-native runtime security project, originally created by Sysdig, and now a CNCF incubating project. It uses eBPF (among other drivers like kernel modules) to tap into system calls and generate alerts for suspicious activity.

- Key Features: Rich set of predefined security rules, ability to create custom rules, integration with alerting and notification systems.

- Use Cases: Intrusion detection, runtime threat detection for containers and cloud environments, compliance monitoring.

5. Katran

- What it is: Katran is a high-performance Layer 4 load balancer developed by Meta (formerly Facebook). It uses eBPF and XDP for its forwarding plane, enabling it to handle massive amounts of traffic with low latency.

- Key Features: Extreme performance and scalability, DDoS protection capabilities, efficient connection tracking.

- Use Cases: Large-scale load balancing for web services and data centers.

6. Pixie

- What it is: Pixie, an open-source project by New Relic (originally Pixie Labs), is an observability platform for Kubernetes applications. It uses eBPF to automatically collect telemetry data (like service maps, resource usage, application profiles, and full-body requests) without requiring manual instrumentation.

- Key Features: Auto-telemetry, in-cluster data storage and query, rich UI for exploring data, scripting capabilities using PxL (Pixie Language).

- Use Cases: Kubernetes application monitoring, debugging microservices, performance analysis.

7. Tetragon

- What it is: Tetragon is an eBPF-based security observability and runtime enforcement platform, developed as part of the Cilium project.

- Key Features: Provides deep visibility into system calls and other kernel events, allows for real-time policy enforcement based on this visibility. It aims to provide security insights with low overhead.

- Use Cases: Runtime security, intrusion detection, process behavior monitoring, file integrity monitoring.

Libraries for eBPF Development:

Beyond these standalone tools and projects, several libraries facilitate the development of eBPF applications in various programming languages:

- libbpf (C/C++): A C/C++ library maintained by the Linux kernel community, providing APIs to load and interact with eBPF programs and maps. It supports BPF CO-RE (Compile Once – Run Everywhere) for better portability.

- gobpf (Go): A Go library that provides bindings to the BCC framework, allowing Go developers to leverage BCC tools and write eBPF programs.

- libbpf-rs (Rust): A Rust library that provides safe bindings to libbpf, enabling eBPF development in Rust.

- ebpf-go (Go): A pure Go library for loading, managing, and interacting with eBPF programs, independent of BCC or libbpf C bindings (though it can work with libbpf-compiled object files).

This ecosystem is constantly evolving, with new tools and projects emerging regularly. The availability of these powerful tools and libraries significantly lowers the barrier to entry for using eBPF and allows developers and operators to harness its capabilities more easily.

Getting Started with eBPF: Your First Steps into Kernel Programmability

Diving into eBPF might seem daunting at first, given its power and close ties to the Linux kernel. However, the ecosystem has matured significantly, offering various tools and resources that make it easier for newcomers to get started. Here’s a guide to taking your first steps with eBPF, catering to different levels of interest and technical depth:

1. Start with High-Level Tools (The Easiest Entry Point)

For many, the most practical way to begin is by using tools that leverage eBPF under the hood, rather than writing eBPF code directly.

-

bpftracefor Tracing: If you want to explore system behavior or debug applications,bpftraceis an excellent starting point. Its DTrace-like syntax is relatively easy to learn.- Installation:

bpftraceis often available in standard Linux distribution repositories. For example, on Ubuntu:sudo apt install bpftrace(ensure your kernel headers are also installed:sudo apt install linux-headers-$(uname -r)). - Simple Examples:

- Trace new process executions:

sudo bpftrace -e 'tracepoint:syscalls:sys_enter_execve { printf("%s called %s\n", comm, str(args->filename)); }' - Count syscalls by program:

sudo bpftrace -e 'tracepoint:raw_syscalls:sys_enter { @[comm] = count(); }'

- Trace new process executions:

- Learning Resources: Check the

bpftracedocumentation on GitHub, which includes a reference guide and many example one-liners.

- Installation:

-

BCC (BPF Compiler Collection) Tools: BCC comes with a suite of command-line tools that use eBPF for various monitoring and tracing tasks. These tools are ready to use and demonstrate eBPF capabilities.

- Installation: BCC can also be installed from distribution packages or built from source. For Ubuntu:

sudo apt install bpfcc-tools linux-headers-$(uname -r). - Exploring Tools: Navigate to

/usr/share/bcc/tools/(or similar path depending on installation) and try running tools likeexecsnoop,opensnoop(to traceopen()syscalls),biolatency(to see block I/O latency as a histogram), ortcplife(to trace TCP connections). - Example:

sudo /usr/share/bcc/tools/execsnoop

- Installation: BCC can also be installed from distribution packages or built from source. For Ubuntu:

2. Understand eBPF Concepts

While using high-level tools, take the time to understand the underlying eBPF concepts. Resources like:

- ebpf.io: The official eBPF website is an excellent resource with introductory articles, documentation, and links to projects.

- Brendan Gregg’s Blog and Books: Brendan Gregg is a leading expert in eBPF and performance analysis. His blog (brendangregg.com) and book “BPF Performance Tools” are invaluable.

- Cilium Documentation: Cilium’s documentation has excellent sections explaining eBPF and XDP concepts, even if you don’t plan to use Cilium directly.

3. Setting Up a Development Environment (For Writing eBPF Code)

If you want to write your own eBPF programs, you’ll need a suitable development environment:

- Linux Kernel Version: Ensure you have a relatively recent Linux kernel (version 4.4+ for basic eBPF, 4.9+ for XDP, and newer versions for more advanced features and helper functions). Most modern distributions meet this requirement.

- Kernel Headers: You’ll need the kernel headers corresponding to your running kernel to compile eBPF programs. (e.g.,

sudo apt install linux-headers-$(uname -r)on Debian/Ubuntu). - LLVM/Clang: Clang is the primary compiler for C to eBPF bytecode. Install a recent version (Clang 6.0+ is generally recommended, newer is better).

sudo apt install clang llvm

- libbpf and Development Libraries: For C/C++ development,

libbpfis the modern library of choice. For Python, you might usebcclibraries. For Go,ebpf-goorcilium/ebpf.

4. Writing Your First eBPF Program (Example with libbpf and C)

libbpf along with BPF CO-RE (Compile Once – Run Everywhere) is the recommended approach for writing portable eBPF programs in C.

-

A Simple kprobe Example (Conceptual): Let’s imagine a very simple eBPF program that counts how many times the

clonesystem call is executed. This is a conceptual outline:minimal_kprobe.bpf.c(eBPF C code):#include <linux/bpf.h> #include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h> struct { // Define a map __uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_ARRAY); __uint(max_entries, 1); __type(key, u32); __type(value, u64); } my_counter_map SEC(".maps"); SEC("kprobe/sys_clone") // Attach to kprobe on sys_clone int bpf_prog_sys_clone(void *ctx) { u32 key = 0; u64 *val; val = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&my_counter_map, &key); if (val) { __sync_fetch_and_add(val, 1); } return 0; } char LICENSE[] SEC("license") = "GPL"; // Important for some helpersminimal_kprobe.user.c(User-space C code to load and read map):#include <stdio.h> #include <unistd.h> #include <bpf/libbpf.h> #include "minimal_kprobe.skel.h" // Generated by bpftool gen skeleton static int print_map_value(int fd) { u32 key = 0; u64 value; if (bpf_map_lookup_elem(fd, &key, &value) != 0) { fprintf(stderr, "Failed to lookup map element\n"); return -1; } printf("sys_clone count: %llu\n", value); return 0; } int main(int argc, char **argv) { struct minimal_kprobe_bpf *skel; int err; skel = minimal_kprobe_bpf__open_and_load(); if (!skel) { fprintf(stderr, "Failed to open and load BPF skeleton\n"); return 1; } err = minimal_kprobe_bpf__attach(skel); if (err) { fprintf(stderr, "Failed to attach BPF skeleton\n"); goto cleanup; } printf("eBPF program loaded and attached. Press Ctrl-C to exit.\n"); while (true) { sleep(2); // Get map file descriptor from skeleton int map_fd = bpf_map__fd(skel->maps.my_counter_map); if (map_fd < 0) { fprintf(stderr, "Failed to get map FD\n"); goto cleanup; } print_map_value(map_fd); } cleanup: minimal_kprobe_bpf__destroy(skel); return -err; }-

Compilation and Running (Simplified):

- Compile

minimal_kprobe.bpf.cto an object file:clang -O2 -g -target bpf -c minimal_kprobe.bpf.c -o minimal_kprobe.bpf.o - Generate BPF skeleton:

bpftool gen skeleton minimal_kprobe.bpf.o > minimal_kprobe.skel.h - Compile user-space loader:

clang -O2 -g minimal_kprobe.user.c -lbpf -lelf -lz -o minimal_kprobe - Run:

sudo ./minimal_kprobe

- Compile

-

Learning Resources: Explore

libbpf-bootstrapon GitHub for template projects and examples. Thebpftoolman page is also very helpful.

-

5. Explore eBPF Project Repositories

Many eBPF-based projects are open source. Browsing their code on GitHub (e.g., Cilium, BCC, Falco) can provide valuable insights into how eBPF is used in real-world applications.

Tips for Beginners:

- Start with a VM: Experimenting in a virtual machine is safer and makes it easier to manage kernel versions and dependencies.

- Read, Read, Read: The eBPF field is evolving. Stay updated through blogs, conference talks (like those from eBPF Summit), and documentation.

- Join the Community: The eBPF community is active. Participate in forums, mailing lists (e.g., bpf@vger.kernel.org), or Slack channels (like the eBPF Slack or Cilium Slack).

Getting started with eBPF is a journey. Begin with high-level tools to see its power, then gradually delve into its concepts and, if you’re inclined, into writing your own eBPF programs. The ability to program the kernel safely opens up a world of possibilities for innovation.

Advanced eBPF Concepts and Future Trends: Pushing the Boundaries

While we’ve covered the fundamentals and common uses of eBPF, the technology also encompasses more advanced concepts and is continually evolving, pointing towards an even more powerful future. Understanding these aspects can provide a glimpse into the cutting edge of kernel programmability.

Advanced eBPF Concepts:

-

BPF CO-RE (Compile Once – Run Everywhere): One of the historical challenges with eBPF was program portability. Because eBPF programs often interact with kernel data structures, which can change between kernel versions, an eBPF program compiled for one kernel might not work on another. BPF CO-RE, heavily reliant on BTF (BPF Type Format) metadata, aims to solve this. BTF provides detailed type information about kernel (and user-space) structures.

libbpfuses this information at load time to perform relocations, adjusting the eBPF program to match the specific kernel it’s running on. This significantly improves the portability of eBPF programs, making them easier to develop and distribute. -

BTF (BPF Type Format): BTF is a debugging data format, similar in purpose to DWARF but much more compact and optimized for in-kernel use. It encodes information about data types (structs, unions, enums, typedefs, etc.) used by both the kernel and eBPF programs. BTF is crucial for BPF CO-RE, enables more accurate introspection tools (like

bpftool), and allows eBPF programs to understand and navigate kernel data structures in a more portable way. -

Global Data and Static Variables: Modern eBPF allows for the use of global and static variables within eBPF programs (e.g.,

.data,.bss,.rodatasections). This simplifies program state management for certain use cases compared to relying solely on maps for all state. The verifier ensures that access to these variables is safe. -

Looping (Bounded): While the verifier traditionally disallowed loops to guarantee termination, recent kernel versions have introduced support for bounded loops in eBPF programs. The verifier can now analyze certain types of loops and prove that they will terminate within a fixed number of iterations. This allows for more complex algorithms to be implemented directly in eBPF, where previously they might have required multiple tail calls or less efficient workarounds.

-

BPF Trampolines (fentry/fexit and fmod_ret): BPF trampolines provide a highly efficient way to attach eBPF programs to the entry (

fentry) and exit (fexit) of almost any kernel function. They are more performant and often easier to use than traditional kprobes for many tracing scenarios.fmod_retallows eBPF programs attached tofexitto modify the return value of the traced function. These are powerful tools for fine-grained tracing and even function call modification. -

User-Space Ring Buffers (BPF_MAP_TYPE_RINGBUF): The

BPF_MAP_TYPE_RINGBUFprovides a highly efficient, lock-free, multi-producer, single-consumer (MPSC) ring buffer for sending data from eBPF programs in the kernel to user space. It’s designed for high-throughput event streaming with low overhead, making it ideal for observability and security monitoring tools that need to exfiltrate large volumes of data. -

Lightweight Kernel Modules (LKM) vs. eBPF: While eBPF offers a safer way to extend kernel functionality, LKMs still exist. Understanding the trade-offs is important. eBPF is prioritized for its safety (verifier, JIT), stability (stable API via helpers), and ease of use for many tasks. LKMs offer more power (can call any kernel function, modify any data) but come with higher risks (can crash the kernel, tied to specific kernel versions, security concerns). eBPF is increasingly covering use cases that once required LKMs, especially in networking, security, and tracing.

Future Trends and Directions:

The eBPF landscape is dynamic, with ongoing development and research exploring new frontiers:

-

Expansion to More Subsystems: Expect eBPF to be integrated into even more kernel subsystems, opening up new areas for programmability. This could include areas like storage, file systems, and power management.

-

Hardware Offload Expansion: While some NICs already support offloading XDP programs, the scope of hardware offload for eBPF is likely to grow. This could involve offloading more complex eBPF programs or extending offload capabilities to other types of hardware, further boosting performance for specific tasks.

-

Improved Developer Experience and Tooling: The community is continuously working on making eBPF development easier and more accessible. This includes better compilers, debuggers, more comprehensive libraries in various languages (Go, Rust, Python), and more sophisticated high-level abstractions.

-

eBPF on Other Operating Systems: While Linux is the primary home for eBPF, efforts like

ebpf-for-windowsare bringing eBPF capabilities to other operating systems. This trend could lead to more cross-platform eBPF applications in the future. -

AI and Machine Learning with eBPF: The ability of eBPF to efficiently collect vast amounts of system data in real-time makes it a potential data source for AI/ML-driven security analytics, anomaly detection, and performance optimization systems. eBPF programs themselves might even incorporate simple ML models for in-kernel decision-making.

-

Enhanced Security Primitives: As eBPF becomes more central to security, expect further development of eBPF-based security tools and more granular control mechanisms within the kernel, potentially leading to more robust and proactive security postures.

-

Standardization and Wider Adoption: As eBPF matures, efforts towards standardization of certain aspects (like program types or helper functions) may increase, fostering even wider adoption across different industries and use cases.

-

WebAssembly (Wasm) and eBPF: There is ongoing research and experimentation into combining WebAssembly with eBPF. This could involve using Wasm as a compilation target for eBPF programs, potentially opening up eBPF development to a wider range of languages, or using eBPF to sandbox and run Wasm modules in the kernel. This is a very active area of innovation.

The journey of eBPF is far from over. Its unique ability to safely and efficiently program the kernel continues to drive innovation, promising even more exciting developments in the years to come.

Conclusion: eBPF - The Kernel’s New Frontier

eBPF has undeniably ushered in a new era of Linux kernel programmability. What began as an extension to a simple packet filter has blossomed into a versatile and powerful technology that touches nearly every aspect of modern system operations, from networking and security to deep observability and performance analysis. Its core strength lies in its ability to allow developers and operators to safely and efficiently inject custom logic directly into the heart of the operating system, responding to events in real-time and providing insights and control that were previously unimaginable without invasive kernel modifications.

The journey through eBPF reveals a sophisticated architecture designed with safety and performance as paramount concerns. The verifier acts as a vigilant gatekeeper, ensuring that only safe code runs, while the JIT compiler transforms eBPF bytecode into highly efficient native instructions. Maps provide the crucial ability to store state and communicate, and a rich set of helper functions offers a stable API to kernel functionalities. This robust foundation has enabled the creation of a thriving ecosystem of tools and projects like Cilium, bpftrace, Falco, and many others, which simplify the use of eBPF and deliver its benefits to a wider audience.

For beginners, the path to leveraging eBPF can start with user-friendly tools, gradually leading to a deeper understanding of its concepts and, for the more adventurous, to writing custom eBPF programs. For experts, eBPF continues to offer advanced features and an expanding horizon of possibilities, pushing the boundaries of what can be achieved within the kernel.

The impact of eBPF is profound. It empowers developers to build more intelligent and responsive infrastructure, security professionals to create more robust and granular defense mechanisms, and performance engineers to diagnose and optimize systems with unprecedented precision. As eBPF continues to evolve, with trends like improved portability through CO-RE, expansion into new kernel subsystems, and even exploration in other operating systems, its role as a transformative technology is only set to grow.

eBPF is more than just a tool; it’s a paradigm shift. It democratizes kernel-level programming, making the Linux kernel more adaptable, observable, and secure. Whether you are building the next generation of cloud infrastructure, securing critical systems, or simply striving to understand the intricate workings of your applications, eBPF offers a powerful set of capabilities to help you achieve your goals. The kernel’s new frontier is open for exploration, and eBPF is the key to unlocking its full potential.

References

Throughout the creation of this blog post, information was gathered and cross-referenced from several authoritative sources in the eBPF and Linux kernel communities. These resources are highly recommended for further reading and deeper exploration of eBPF technology:

-

eBPF Official Website (ebpf.io): The primary source for eBPF information, including introductions, documentation, project landscapes, and community resources.

-

Cilium Project Documentation: Cilium, a leading eBPF-powered networking, observability, and security solution, provides excellent in-depth explanations of eBPF concepts and architecture.

-

Wikipedia - eBPF Page: Provides a good overview of eBPF history, design, and adoption.

-

Tigera Guides: Tigera, the company behind Project Calico, offers useful guides and explanations on eBPF and its applications.

-

Brendan Gregg’s Website and Publications: A renowned expert in system performance and eBPF, Brendan Gregg’s blog and books are invaluable resources.

-

Linux Kernel Documentation: For the most definitive information, the Linux kernel’s own documentation on BPF (found within the kernel source tree) is the ultimate reference.

-

Various eBPF Project Repositories: The GitHub repositories for projects like BCC, bpftrace, Falco, libbpf, etc., contain code, examples, and further documentation.

This list is not exhaustive but provides a strong starting point for anyone looking to learn more about eBPF.

Happy Hacking!!

Tag or DM me if you learned something

Comments